Jean Michel Frank: the Design of Nothingness

Words: Marco Marino

Translation: Carlotta Buosi

Jean Michel Frank was born into a wealthy Parisian family of jewish bankers - his cousin Otto Frank was Anna Frank’s father - in 1895. His father was German and his grand father from his mother side was a rabbi in Philadelphia. A skinny, sensitive teen ager with aquiline nose, he first signed up to study Law at university, but after the tragic death of both his brothers - who lost their lives fighting in World War One - and his mother, followed by his father’s suicide, Frank suddenly found himself alone and orphan and decided to leave Paris to travel.

He spent a few years between Venice and Niece, where he had the chance to meet some of the most influential exponents in the fields of arts and culture of his time, such as Igor Stravinsky and Diaghilev, Aragon Eluard, Christian Bernard and Pablo Picasso. It was Picasso himself who introduced Frank to the most significant figure for his future formation as an interior designer: Eugenia Errazuriz. Known for her eccentric choices of interior decoration, especially for her Parisian apartment - wicker baskets in the main entrance, grey painted wooden hangers in the living room, a white closet chosen for its geometric proportions - the rich Chilean widow introduced Frank to the high profile Parisian world, but also noticed his potential.

The apartment in Rue de Verneuil, which he himself decorated, conquered Errezuriz, who described it as ‘a soft combination of travertine, sandblasted wood, parchment and distressed leather.’ Frank’s inspiration came from the interior design of traditional Japanese homes, free from useless decorations and perfectly proportioned in its elements, each one taking a certain amount of space in harmony with everything else around it.

Still, the full embodiment of the Japanese style was not the most innovative element in Frank’s work, thanks to Errezuriz, who also introduced him to the French decorative art of the XVIII century, the way materials were treated at that time and the millimeter precision of French artisanal decorations.

In 1932, Jean Michel decided to open a shop in Faubourg Saint Honore, along with artisan Adolphe Chanaux. The first a melancholic child of Parisian bourgeoisie, the second a family man - skilled in his art and expert of business - they had extremely different personalities, but together they created some of the most significant pieces of design of the 1930s, rediscovering the techniques and crafts of traditional French decor.

Varnished straw - typical of the Marie Antoinette period - wall paper made of parchment, left overs of Hermes leather used to create incredibly soft sofas and potato bags to coat pillows were just some of the most inventive creations of the duo.

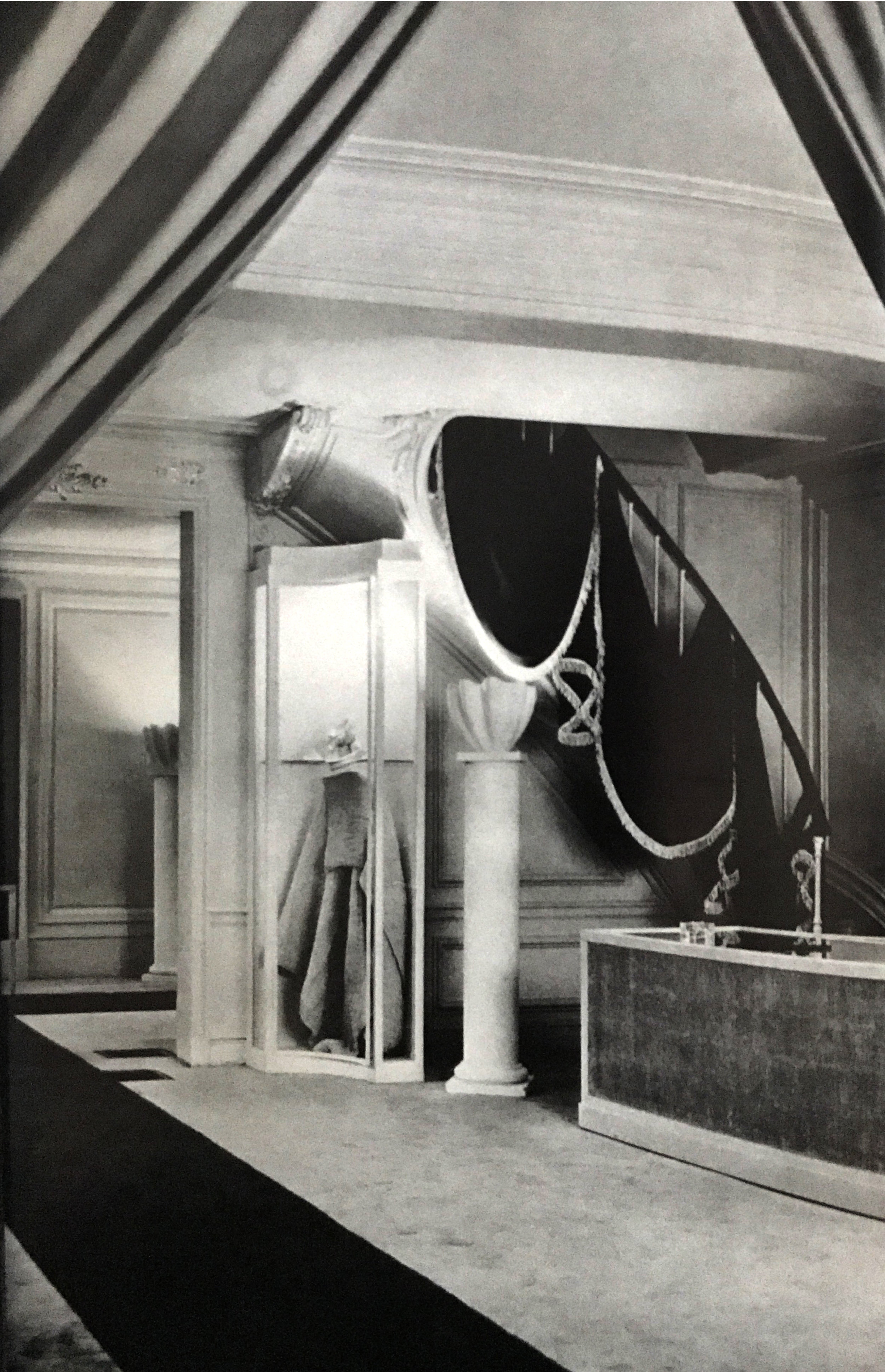

Another significant figure that helps us comprehend Frank’s style is Elsa Schiaparelli. The Italian fashion designer who surrounded herself with surrealists for the likes of Salvador Dali’ - Frank designed the first lip-shaped couch for him - and the Giacomettis, commissioned him the interior design of her boutique in Place Vendome, in 1937.

Frank installed a bamboo cage in the middle of the store, while the window overlooking the Place - positioned asymmetrically with the inside space - was a chance for Frank to study a way of regulating the symmetries through optical effects. He manipulated a delicate structure to trasfigurate the inside environment, creating a space within the space in a playful continuous of perspective remarks with the cage as focus point, able to alter the perception of the elements surrounding it through its vertical lines. The lines themselves transform the space, creating a delicate structure where the symmetries are constantly in the background, but they don’t suffocate the visitor.

Economy of means and the strive for perfection are the real contributions of Franks’ work to the world of design: his capacity to fairly juxtapose all the elements coexisting in the same space, his deep acknowledgement of the secret code upon which every measurement is dependant, his way of establishing hierarchies within the space: the height of a couch is what determines the length of a carpet, which also generates the proportions of a table and the lamp placed on top of it.

Frank’s ensembles portray the elegance of putting together what is there with that isn’t, his interiorsfocused on highlighting the vacuum through geometric simplicity, which sharpens the environment’s constructive lines.

Just as silence plays a key role in music, the vacuum is therefor an integral part of Frank’s work.