Issue 10: Compulsory Party / Passive Aggressive

EDWARD MITTERRAND

PHOTOGRAPHY BY SIMON SCHWYZER

INTERVIEW BY LYNA AHANDA

Edward Mitterrand is an art advisor to individuals and companies. A prestigious profession that requires to explore art from an economic and emotional perspective but also a high level of taste and discretion. His commitment to art is precise and unpretentious. In an industry where the standards of what is attractive constantly evolve, Mitterrand tries to lead his clients to an aesthetic awareness they didn’t even know existed.

How did you first approach working in the art world?

I was working in marketing and my father asked me if I would move to La Jolla in California to run a gallery and stay close to Niki de Saint Phalle who had just moved there herself for health reasons. I went but didn’t stay. I thought La Jolla was just boring, but ended up working with my father in Paris as a freelancer, working on monumental sculpture exhibitions for cities such as Vancouver, Kaoshiung, Rio.

Was there anyone or anything you looked up to early on?

I had been very impressed by Jean Tinguely and Niki de Saint Phalle when I met them. For me they were the essence of freedom, creativity, energy, beauty, strength. The essence of what art should be. I remember visiting the Venice Biennale for the first time and being very impressed by two works: Jeff Koons’ sculpture of him and Cicciolina and Ashley Bickerton’s survival modules; my first strong interaction with contemporary art after Niki and Jean.

What makes a piece of work successful for you?

Well there is successful for the art world and then there is successful for me. For the art world, especially nowadays, it’s often a question of value and media exposure. Sometimes for good reasons. For me the good reasons can be wether the work represents the overall work of the artist or a portion of it, if it is a particular eye or portrait on a specific moment of our time and society, if it’s an intelligent continuity or a rupture towards the past.

How do we look at art critically?

Usually your eye is attracted, which is not the best critic, so it’s then recommended to read about the artist’s intention and find out if it makes sense as an intention and if the work serves that intention. Is it a new form of language? It does not need to be a revolution, just a different way of expressing things, something you haven’t seen in any of the hundreds of shows and art fairs you visited over the years.

When does the process of buying art become satisfying?

When you’ve waited for a specific artwork for a long time, either because you couldn’t find it or because you couldn’t afford it. When you are buying for a client and you are convinced it’s a great work and also a great work for him/ her, that is going to bring more than just an aesthetic but a whole new world for him/her, that is the beginning of something and not the end of the course. It gives me the feeling that I’ve helped, I’ve participated in the discovering of something new and wonderful for someone. It’s never the value, although of course I’m glad when I am making the right choice for my client also in terms of money, but usually if it’s as good as I hope it will be worth more, the question is after how many years.

Do you still come across new artists? Is your work somehow intuitive?

A lot, constantly, through shows and art fairs I visit and from reading specialised press, printed or web. The intuitiveness is crucial, although it’s of course fed by learning and seeing, without it it would only be about following the market, which is often a very bad idea.

What gives your gallery an international dimension?

I am only a detached art director for the gallery, but since I also happen to have shares of it I’ll consider it’s “mine”. I’m interested in the relationship that the gallery, and my father who built it, have built over the years with sculpture. That’s the expertise that gives it an international edge. But that’s only the intention, then it’s about the artists, the ones you choose but essentially the ones who choose you, that’s when you know you accomplished something. The Domaine du Muy has certainly been an accelerator in bringing more international attention to our attachment to sculpture.

Over the past five years, which artist has made the biggest impact on you?

Choosing one would be a treason to too many others. Over the recent years I can say Rashid Johnson, David Altmejd, Christopher Wool, Blair Thurman.

Do you feel like technology facilitates everything?

It certainly facilitates the spreading of information, but it’s too much information to treat. Controlling, qualifying and treating so much data is only possible for computers and my brain is very far from being computerised. I choose a few tools for specific needs and try to stick with them. MailChimp for sending newsletters, Artnet for checking auction results, Paperless for sending invitations, Artsy for one way of looking for works.

Do you think that people are more “art educated” now?

More people think they are. And the more they think they are the less they make true efforts to educate themselves. As an art advisor it’s my job to show them how little they in fact know and how much they in fact need me.

What makes a great artist?

Him or herself essentially. How much courage, confidence, strength an artist has to endure the toughness of the empty canvas, the lack of recognition. But also, as always, strong work, seeing other shows, confronting with other artists.

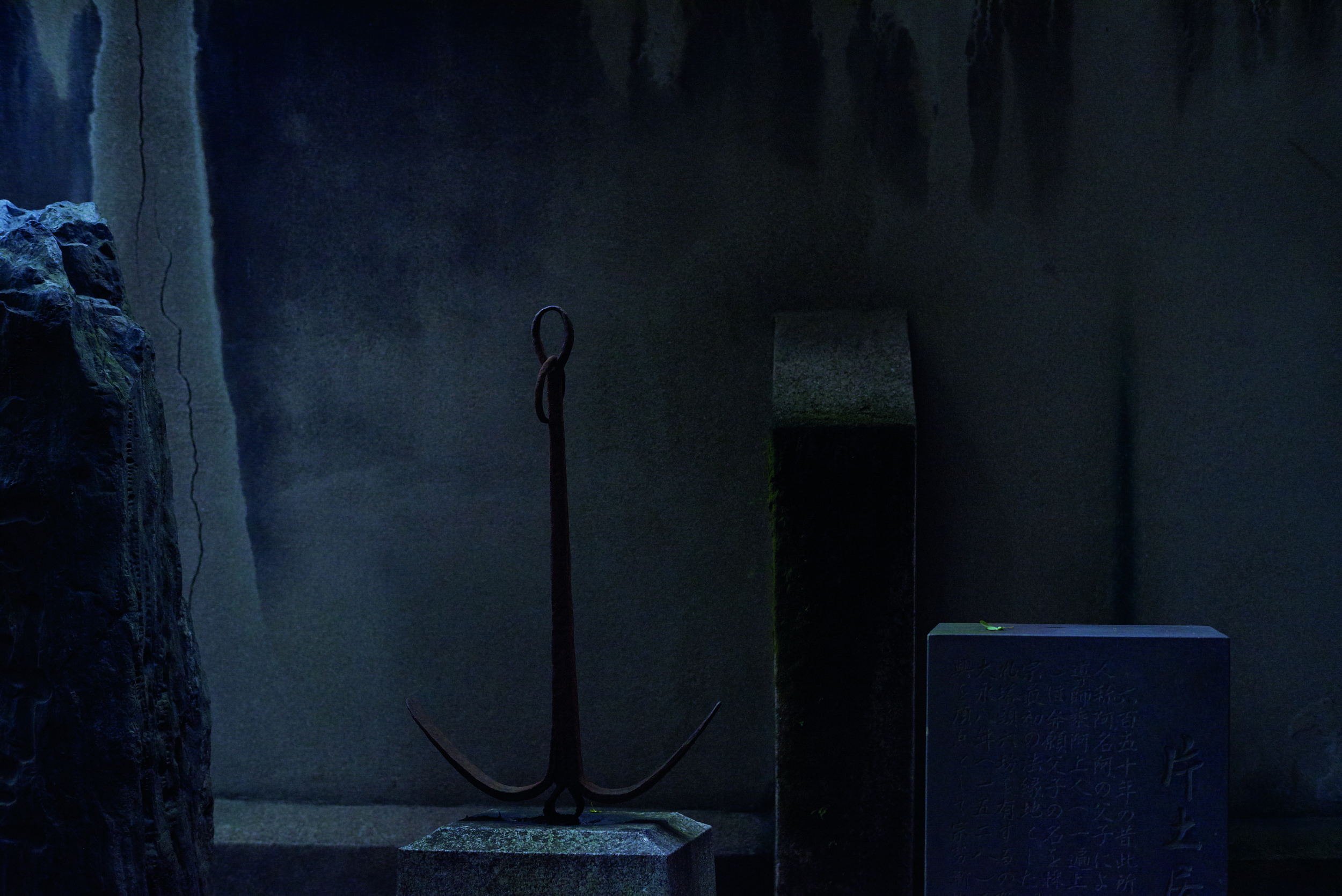

What is your goal with Domaine du Muy?

We have various goals. Build a vitrine for our expertise in monumental sculpture in order to convince potential clients (cities, companies, institutions, large project builders) to talk with us about placing monumental sculpture within their environment. Convince new artists to work with us on new projects, in the gallery and/or elsewhere. Work in the South of France, close to the sea, within nature, in a house which is also an office, with clients but also friends and artists and collectors.

Do you think that artists are in need of broader ideas?

No, I think artists are the ones with broader ideas, but we can offer them a different kind of experience. The Domaine du Muy has an approach to nature and art which is I think quite specific, very unsophisticated, we want that nothing comes in between that relationship.

Of seeing their work in a wilder context?

Yes, that. The confrontation to blunt nature, the interaction, the encounter. Whatever the result it’s always interesting, it rarely fails; we are just placing the works there, they do the rest with the surrounding nature. No artificial flavour needed.

Hotel Tokyo / Yoshiyuki Okuyama / Hadarrah More